Discography

1953

Please Mr. Right Man

Tantalizing Melody

Lucy Reed recording on the Chance Label with the Al Trace orchestra: “Please Mr. Right Man” and “Tantalizing Melody.”

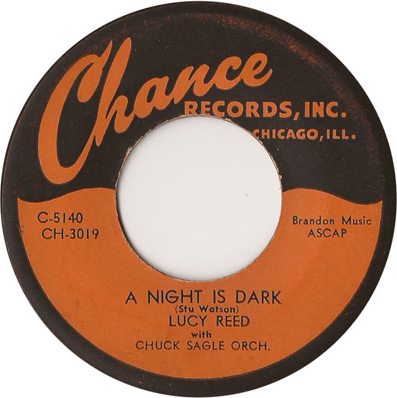

1954

A Night is Dark

Au Revoir

Lucy Reed recording on the Chance Label with the Chuck Sagle orchestra: “A Night is Dark” and “Au Revoir.”

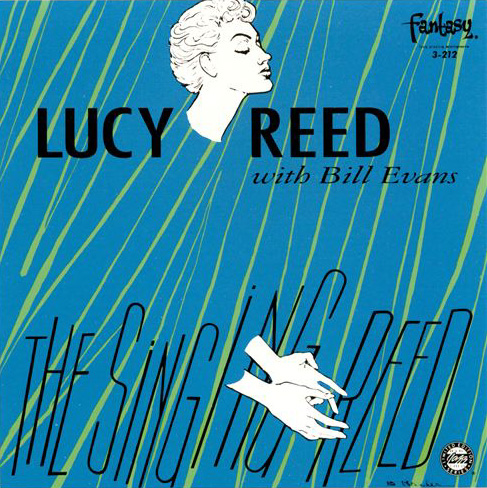

1957

The Singing Reed – Fantasy Records

Fantasy Records full album release featuring:

Fantasy Records full album release featuring:

Lucy Reed -Vocals

with:

Bill Evans – piano

Howard Collins – guitar

Bob Carter – bass

Sol Gubin – drums

(Recorded in New York – August 13-15, 1955)

on selections #4, 6 and 7 with:

Dick Marx – piano

Johnny Frigo – bass

(recorded in Chicago – January 18, 1957)

| Side 1 | Side 2 |

| Inchworm (Loesser) | Flying Down to Rio (Kahn-Eliscu-Youmans) |

| My Love is a Wanderer (Howard) | Little Girl Blue (Rodgers-Hart) |

| Because We’re Kids (Hollander) | Fools Fall in Love (Berlin) |

| It’s Alright With Me (Porter) | Out of This World (Mercer) |

| There’s a Boat Dat’s Leavin’ Soon for New York (Gershwin) | You May Not Love Me (Van Heusen) |

| It’s a Lazy Afternoon (Moross-La Touche) | My Time of Day (Loesser) |

Bonus Tracks on CD re-release:

“Tabby The Cat,” “Baltimore Oriole,” and “That’s How I Love the Blues”

Liner Notes – The Singing Reed

Taste is one of those words which is being battered out of shape nowadays; battered in ad copy, over-familiar essays and general criticism, to say nothing of liner notes. Taste excuses all those things you do like and damns those things you hate. It can be written about with forensic skill, as if the fate of the British pound sterling depended largely on one’s ecstatic appreciation of some such unworthy thing as the number of buttons on one’s blazer, or the exact it suggested by Clara Bow’s IT. On the other hand, it has its place, however tenuous, in the more gushy style of prose where lesser things like houses and cars and objects of art are described with almost the same vapidity that is given to, say, mortuary policies.

Taste may also be described, though not by me, in such a line as the following by a sometimes too well known author – wherein he makes love to dry lines, to say the least: “Did you ever eat a peach on a beach?” That has a certain taste, of course; the line, not the peach; but, as any school boy knows, the important thing, the real test of taste, is whether you put the peach pit in the trash basket on the beach; which entails a certain respect of humankind besides.

All of which should prove that I know what I’m talking about when I use the word taste to describe Lucy Reed; at least, that I’m granting all sort of latitude to the word, but still sticking very much to my guns. For me, and for hundreds like me, Lucy was, for several years, the one warm ray of sunshine in the sprawled city of Chicago. She sang, then, at the Lei Aloha Club, one of those strange out-of-the-way clubs where nothing would ever be happening in any other city except Chicago.

But very much happened there. The audience for one thing. Chicago musicians seemed almost self-destructive in their shilling for the joint. “Have you heard Lucy,” was the question asked every jazz traveler, and, if the answer were no, anything, including a finely detailed map, was done to get you there for the Monday and Tuesday night sessions with Lucy and pianist Dick Marx and bassist Johnny Frigo.

And if you overcame the disappointment of your first impression of the club – the horseshoe bar, the tiny tables, loud noises, blaring juke and shirt-sleeved citizens – you’d appreciate that trouble. For, when the great lights dimmed ever further and the bartender lowered his silver shaker, a fantastic hush would fall over the entire barroom, noisy characters would be shamed still, even the air conditioner changed from its steady wheeze to a more moderate mumble. Dick and Johnny would come onto the minute stand at the mouth of the horseshoe bar – come on, too, with a wonderful brand of humor and swing with excitement – all by their twosome. Then, if it was your first time there, you would be surprised as the lights went out completely and a voice asked, and asked melodiously, “Love for Sale,” asked it and sang that song while skirting around the bar, ending in front of the bandstand for the last words and for a triumphant, eye-smarting focus of a baby spot, dead until then. The regulars were used to it, of course; it didn’t happen in every show, in any case, but when it did, it had the kind of show-business validity that’s nothing but taste.

That was Lucy Reed. As a matter of fact, it is Lucy Reed, who is thirty-three years old (“That’s a bad thing to say when I’m just getting started”), who was born in Marshfield, Wisconsin, went to high school in St. Paul, Minnesota, and spent much of her life after that, traveling to Iron City (Iron Mountain), Michigan.

Lucy began as a pop singer, married a jazz drummer, listened to early Garroway shows and, finally, developed a real taste for jazz. When her husband was killed over Germany, he went back to Iron City (Iron Mountain), still listening attentively, still very much concerned with music and with what musicians could teach her. Then, after two years of that exile, she was booked into a Milwaukee club, then to Duluth, then into Woody Herman’s band when Woody passed through that latter city. She left woody to join Charlie Ventura, remaining with him until he disorganized in Chicago. There was scuffling again, of course, but Lucy finally landed a job at Chicago’s Streamliner with organist Les Strand. It was there that she met bassist Johnny Frigo, who had just left the Softwinds. And, when the Lei Aloha offered her a job, she turned first to Johnny and then to pianist Dick Marx: “I heard him for the first time at the club,” she remembers, “and I just wanted to wail.” And wail she did, so did they all, for over two years with the aforementioned warming results.

All three had the same conception, were anxious to show each other off in the best possible light. It was a happy group and it gave the right depth – you can hear it on many of these tracks – to a woman who seemed in love with the composer and lyricist of every song she sang. She sang then, as she does here, just what she wanted to sing and the way she wanted to sing them; songs with story-lyrics, most often; sometimes songs which were cut out of Broadway productions in their try-outs in Hartford. To all she gave her warm, womanly voice, capable of the finest nuances, structured by her own feeling for simplicity.

You can hear something of what I’ve written – as much as records will do, at least – when the three are together here on this LP: It’s All Right with Me, It’s a Lazy Afternoon, and Flying Down to Rio. But the best of Lucy for me is reserved for her New York group – pianist-arranger Bill Evans, guitarist Howie Collins, bassist Bob Carter and drummer Sol Gubin – and particularly, on four out of that batch: Inchworm, My Love is a Wanderer, Because We’re Kids, and My Time of Day.

There’s nothing wrong with the others, far from it; but if I’m allowed to throw my taste around, and why not, those would be my choices. Worm and Day are two of Frank Loesser’s best, the former, his avowed favorite, the latter from Guys and Dolls. Wanderer has a real folk music quality, hauntingly written by Bart Howard. Kids is that wonderful, kind of philosophical song, with lyrics by Dr. Seuss and music by Frederick Hollander from the motion picture Five Thousand Fingers of Doctor T.

Certainly you’re free to pick and choose elsewhere among these tracks, and choose you will, whether it be Little Girl Blue, with it’s attractive triplet background behind the words “Now the young world has grown old/Gone are the Silver and Gold,” or Boat, for it’s engaging swing in Lucy’s voice, or You May Not Love Me, because of it’s spare melancholy.

But your choice is bound to be governed by Lucy’s particular effect on you as happy, or loving, or distraught, or whatever else you may feel from these tracks. Unquestionably you will know that she is a woman, which is something of a novelty in the realm of the specialty stylist. Always, you will be conscious of her warmth and grace which give a myriad of delicate shadings to the fine lyrics she sings. And for that time, you can live in a world where there are glowing fires, mulled ale, rich understandings, and this red-haired lady to give it meaning.

~ Bill Coss – Editor, Metronome Magazine

1958

This is Lucy Reed – Fantasy Records

| Side 1 | Side 2 |

| There He Goes (English) | Little Boy Blue (Field-D’Hardelot) |

| Lucky to Be Me (Bernstein-Comden-Green) | A Trout, No Doubt (Kadison-Howell) |

| In the Wee Small Hours (Mann-Hilliard) | Born to Blow the Blues (Siegel-Russell) |

| St. Louis Blues (Handy) | This Is New (Weill) |

| Easy Come, Easy Go Lover (Heyman-Green) | No Moon at All (Mann-Evans) |

| Love For Sale (Porter) | You Don’t Know What Love Is (Raye-DePaul) |

Fantasy Records full album release featuring:

Lucy Reed -Vocals

with: Gil Evans – piano and arrangements

Jimmy Cleveland – trombone

Bill Pemberton – bass

Romeo Penque – alto flute and English horn

Tommy Mitchell – bass trombone

David Kurtzer, bassoon

George Russell – drums

Harry Lookofsky – tenor violi

on “Love for Sale,” “A Trout No Doubt,” and “No Moon at All”

(Recorded in New York -January 1957)

with:

George Russell – drums and arrangements

Art Farmer – trumpet

Romeo Penque – flute and English horn

Sol Schlinger – bass clarinet and baritone

Milt Hinton – bass

Don Abney – piano

Barry Galbraith, guitar

on “In the Wee Small Hours of the Morning,” “Born to Blow the Blues,” This Is New,” and “There He Goes” (arrangement by Jack English)

(Recorded in New York -January 1957)

with

Eddie Higgins – piano and arrangements; Willaim Gaeto, Verne Rammer, John Gray and Ken Soderblum.

on “Lucky to Be Me,” “St. Louis Blues,” “Easy Come, Easy Go Lover,” “Little Boy Blue,” and “You Don’t Know What Love Is”

(Recorded in Chicago – January 1957)

Liner Notes – This Is Lucy Reed

Let us not, to begin with, get hung up on the subject of what a jazz singer is. Not this time, anyway. The only woman I know, in fact, who is above the semantic war, is Billie Holiday. She even talks jazz. Let us say about Lucy Reed that she has certainly been influenced by jazz, and that no jazz musician I can think of would feel it a drag to play with her. She is, to end the definitions, a fine-grained, intelligent, and sensitive (without a capital S) singer.

In this, her latest collection, there is another quality – or rather, intensification of a previous quality – that makes this for me her most satisfying recital on records. I have been bemused by Lucy since I first heard her a couple of years ago at the Village Vanguard in New York. I had, for reasons that escaped me even then, been spending a lot of time in the “intimate” rooms and had been hearing either weary sophisticates with appalling amounts of makeup or shiny young nubiles who looked as if they had just arrived from Mount Holyoke and had probably given an English instructor there a hard time. The sophisticates had a good repertoire, had a point of view about the lyrics (however brittle) but couldn’t sing very well. The nubiles were remarkably energetic, knew a few good tunes along with some very special material indeed, and also couldn’t sing very well.

Lucy, slim and startlingly unaffected, was modest in dress and demeanor. She stood at the microphone, and just sang. Somehow she had assembled a repertoire that wasn’t entirely overfamiliar (some songs have been so perseveringly rescued from neglect that it would be refreshing if they were lost again). Most important, of course, was that she was a singer. She wasn’t selling sex or “personality” or wrought iron wit (to paraphrase Mort Sahl). She was telling her story, the way a jazz musician does, and she was telling it warmly and with thorough honesty.

The only quality I would have particularly liked somewhat more of – and this applies to her otherwise valuable first Fantasy LP – was more strength, more open emotion in those songs and spaces that called for outspoken heat. She has that power now, not only in the more palpable sense, as the way she plunges into “St. Louis Blues” and “Love For Sale” here, but all through the program. There is an added tensile strength, rhythmically and in terms of emotional projection, that puts into relief more clearly than ever before the essential fact about Lucy that she is singing what she knows, what she has learned in hurting and wanting and sometimes getting. This is not, as is oppressively often the case, a singer imposing a “style” on her material from without and hoping to arrest the attention by the novelty of that “style” or by the “newness,” Lord help us, of her “sound.” This is a woman who has a 14 year old son, lost a husband in the war, is married again, has scuffled long years in search of recognition and self-fulfillment, and who will never be lucratively “commercial,” because singing her own way means too much to her, is too valuable a means of self-expression for her to grasp for the hits or con herself.

“I never sing,” she told Down Beat’s Don Gold, “anything that doesn’t kill me when I hear it… I feel I go home as tired as a horn player, because I’m so closely linked, emotionally speaking, to the tunes I do. I find songs that mean so much to me, too, because I’ve had experience, more than many of the younger chicks singing today. I’m 35. The tunes are meaningful to me because I’ve lived them.”

Having talked about Lucy, it might be time to examine the perspective of the arranger who provides accompaniment for a singer of sense and sensibility. George Russell, one of the three arrangers for this set, is better known as one of the very few modern jazz composers who really does compose and who has something individual – and with strong jazz roots – to say.

A rather ingenuous columnist for The Village Voice, a valuable Greenwich Village weekly, recently asked George the difference between an arranger and a composer. It’s around $.95,” he answered. “Union scale is $4.60 per four-bar page for composition and $3.65 for arrangement. But seriously, it’s the x-factor. In arranging, you are given something to start with, and in composition you start with a blank page.”

While the challenge is admittedly greater when composing, there are areas of arranging, George and other composers agree, that present stimulating problems to the inventive arranger.

Gil Evans recently talked about the area that is concerned with providing a vocalist with optimum background. Gil, who is a composer, has been a vital, though largely unpublicized influence on much of modern jazz (see The Birth of the Cool, Down Beat, May 2 and May 16, 1957). He is a deeply conscientious writer who is constantly exploring new ways of expressing the illimitable shading of meanings that are possible in music.

“For the arrangements I did for Lucy,” Gil points out, “I used a combination of instruments I’d never utilized before. It took me a long time to decide on it. I wanted to get a jazz feeling, but I didn’t want to use loud jazz instruments. For body and depth, I used the bassoon and two trombones. For the top part, I wrote in flute and violin. I had heard Lucy’s first LP, and to get further acquainted with the way she sang, I invited her to my apartment and we went over the songs.”

Gil spoke in general terms about three of the several ways to write accompaniment. What he said applies in parts to this record, but also may orientate your listening to other vocal sets. “There are so many possibilities for accompaniment. The vital consideration in accompaniment, however, is the rhythm placement of a melody to fit in with the singer’s rhythm placement. Rhythm placement determines much of a singer’s style. The term you hear, however, usually is that her ‘time is good.’

“A singer’s style begins, of course,” Gil continued, “with her taste. Her taste is reflected in the basic sound she originally selects and in what she does with it in terms of rhythm placement and in other ways in which she adapts her sound to the needs of the tune. If you become a good singer, you learn to modify your basic sound to what the song calls for, to the particular feeling and idea of each song. You add or subtract, put an edge here or move it out there.

“Returning to writing accompaniment for a singer, I mean accompaniment that is designed for a particular singer. Some records use standard accompaniments that are atrocious. You’d swear that the singer had just come into the studio and just met the arranger. On records like those, you don’t hear any complementary things going.

“Now,” Evans went on, “here are three ways to work out rhythm placement of the melody for a singer. You may, for one thing, be so familiar with her style that you can place things at strategic point, things you know will fit in with her rhythm placement. You can do this by writing complementary rhythm figures, chords, etc. You can utilize these methods of propulsion, which is one of the reasons for accompaniment; or you can write so as to slow things down at those places that need it. All arrangements have a certain amount of diving in and out, but all also have to come out in the clear and allow things to flow rather peacefully at times.

“Another way, if you don’t know the singer’s style that well, is to have her sing for you and notate where the rhythmic placement is, providing you’re relatively sure that’s the way the singer will do it when you record. With that knowledge, you can write around the placement, and can work in a complex, weaving texture around her.

“A third way is to write in sustained chordal and/or linear accompaniment without much activity, and let the rhythm section, on hearing the singer at the date, take care ad lib of the vital complementary function beyond what’s written.

“I think elements of all three methods can be found in most arrangements, including the one’s I did for Lucy.”

Gil arranged and directed “Love for Sale,” “A Trout No Doubt” and “No Moon at All.” George Russell was in charge of the backgrounds and directing for “In the Wee Small Hours,” “Born to Blow the Blues,” and “This is New.” “There He Goes” was arranged by Jack English and Eddie Higgins charted the others.

The Evans and Russell sessions took place in New York in January, 1957. Gil was on piano for his date with Jimmy Cleveland, trombone; Bill Pemberton, bass; Romeo Penque, alto flute and English horn; Tommy Mitchell, bass trombone; David Kurtzer, bassoon; George Russell, drums; and Harry Lookofsky playing a tenor violin (an octave lower that the usual violin) and probably the only one of it’s kind in New York.

The Higgins session was held in Chicago, also in January with Higgins on piano and William Gaeto, Verne Rammer, John Gray and Ken Soderblum completing the quintet.

George Russell played drums on his date with Art Farmer, trumpet; Romeo Penque, flute and English horn; Sol Schlinger, bass clarinet and baritone; Milt Hinton, bass; Don Abney, piano; and Barry Galbraith, guitar.

~ Nat Hentoff, co-editor, Hear Me Talkin’ to Ya and Jazz Makers

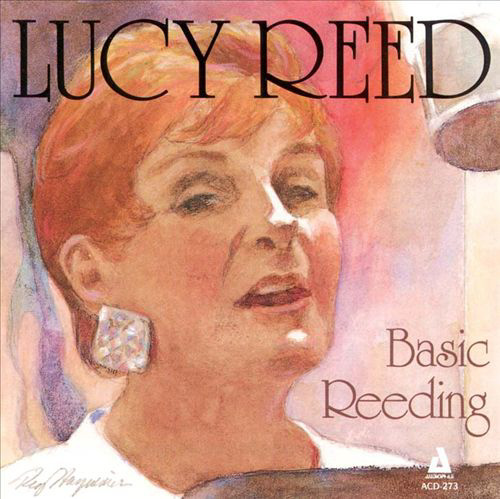

1991

Basic Reeding – Audiophile

| You’re the Cause of it All (Orlando Murden) |

| The Touch of Your Lips ( Ray Noble) |

| I Told Ya I Love Ya (Lou Carter-Herb Ellis-John Frigo) |

| Pete Kelly’s Blues (Sammy Kahn-Ray Heindorf) |

| A Child is Born (Thad Jones-Alec Wilder) |

| The Umbrella Man / The Gravy Waltz (James Cavanaugh-Larry Stock-Vincent Rose / Ray Brown-Steve Allen) |

| I Ain’t Got Nobody (Roger Graham-Spencer Williams) |

| The Swing Song (Carroll Coates) |

| Winter Moon (Hoagy Carmichael-Harold Adamson) |

| Get Outta My Life, Baby (Allen Toussaint) |

| The Music Machine (Richard Rodney Bennett-Frank Underwood) |

| One Morning in May (Hoagy Carmichael- Mitchell Parrish) |

| Lulu’s Back in Town (Al Dubin-Harry Warren) |

| Young and Foolish (Arnold Horwitt-Albert Hague) |

Lucy Reed -Vocals

Larry Novak – piano

Ray Brown -bass

Herb Ellis – guitar

(Recorded in Chicago at Universal Studios -1991)

Liner Notes

As Lucy Reed sings and gently swings, it all comes back. How long ago was it I first heard Lucy sing? The fifties had just begun and the lyrics of songs had really counted for something. To me and others seated around the bar, long buried feelings were tapped. Sure, the music was there, but those words got you: bittersweet one moment, ebullient the next. It took a certain kind of singer to put them forth with the grace they observed. Lucy was one of them. When she sang Love For Sale, we felt for the girl who was selling it. We knew and understood her. And when she sang Inchworm, the world was young again. And so were we.

On Friday nights, my colleagues of early Chicago TV days would wander into the Streamliner. It was a lounge near Union Station. We didn’t need any 20th Century Limited to take us to the Big Apple or a milk train to Keokuk. As we nursed our drinks, Lucy transported us to cities and small towns and we met the lost girl. The memory of Lucy Reed and her touchingly gifted colleagues, Audrey Morris, Lurlean Hunter, Dick Marx and the ever-contemporary Johnny Frigo, is indelible. Those were sweet evenings going into a mellow midnight.

How long ago was it? Long enough for mad military adventures to drive us all crazy; for high technology to drown out those lovely words; for computers to replace the human touch. In this fine album, Lucy brings us back to our felt selves. It is not a clinging to the past I’m talking about. That does no one any good. It is a remembering. That is altogether something else.

Lucy Reed is no longer the young woman she was back then. No, she is an older person, whose artistry has taken on a mellow tone; whose life and experience has added a deeper meaning to those wonderfully-wrought lyrics. Here are Alec Wilder and Hoagy Carmichael and Harry Warren and their talented contemporaries sung again and born again. Here is an album to treasure.

~ Studs Terkel